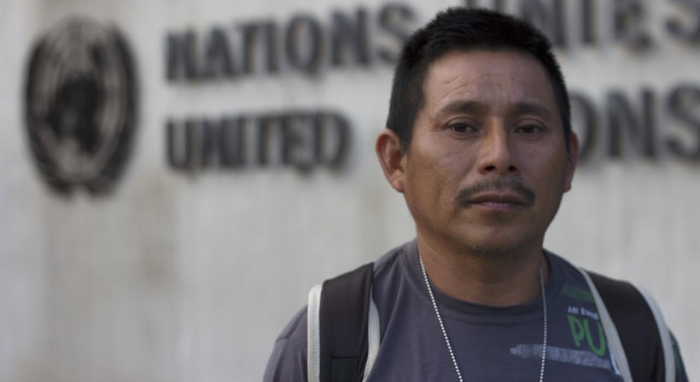

Francisco Javier,

member of the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras

(COPINH), talks about the role of UN mechanisms in combatting the ongoing

impunity in investigations into the murder of Berta Cáceres, and emphasises

that risks for her colleagues are only increasing.

Lea este artículo en español aquí.

In response to the

ongoing threats against human rights defenders in Honduras, ISHR, along with

169 organizations and 16 academics, recently sent a letter to the

Attorney General Office and the Ministry of

Human Rights, Justice, Interior and Decentralisation in Honduras

calling on them to comply with their international human rights commitments.

You are a human rights

defender in Honduras, advocating for environmental and land rights, can you

tell us a bit about the human rights work you do?

We speak for indigenous

populations about protecting our common goods. We want to protect the forests,

river and air, and also our territories. COPINH has built capacity among

indigenous populations to help them understand that we are here to take care of

the gifts of nature – that we must defend the little that we have, otherwise

the nature will become a desert. As human rights defenders we have this obligation

and commitment to give support to other communities and indigenous peoples in

Honduras and in other countries. For example, we have colleagues in Panama

who are suffering the same challenges that we are. We’ve come here to talk

about these things, and to fight – not just for today

and

tomorrow, but for the generations to come, so that they may also be defenders

of natural resources.

What

motivated you to become involved in human rights work?

I am

only beginning; I started in 2013. COPINH was working with us and helping us to see our shared objective:

to defend nature. In each community, you will hear the same concerns: that the

rivers and forests – which are life for us – are being destroyed when they come

to construct mines, dams, and other deadly projects. In COPINH, we share this

information with communities, helping them to understand, so that all

indigenous peoples in Honduras can unite.

What challenges or risks

do you face as a human rights defender in Honduras?

Because we speak the

truth, they want to shut us up. They threaten to kill us because we tell the

truth. It is companies and the State that threaten and attack us; they don’t

like that we defend Mother Earth. When we denounce what seems wrong or unjust,

about when our decisions are not respected, that’s when we face risks. That’s

when they could kill us. But they won’t silence us. Even though they killed Berta

and other colleagues, we – and anyone else who joins us – raise our voices so

that we continue to grow. The spirit of Berta and our other comrades

accompany us. Because we are defending life

itself.

It may bring more threats, but they won’t silence us. We will continue, and

those who remain, and the generations that come, we will teach them to do the

same as us – to speak out for our rights.

Do you work a lot with

other organisations working to protect human rights defenders – national,

regional or international?

Yes, we’re very proud

because many organisations have given us support nationally and

internationally. We are very happy that we are not alone, that there are

people of goodwill who provide such support. When we come to Geneva, we feel at

home; we’re looked after.

What is the legislative

framework like for human rights defenders in Honduras– are there laws that

are applied abusively?

Human rights defenders are

prevented from speaking. The laws on free, informed and priorconsultation

aren’t being complied with in Honduras. Criminal laws are used against

indigenous peoples unjustly to criminalise us, and the judicial system supports

the companies, like DESA. Neither our autonomy nor our rights are respected.

When we speak the truth, the police and the military are set on us, and

sometimes they beat us. We want the military and police to leave

our territories. It’s not easy for us to speak out because it makes our lives

very challenging. They criminalise members of the indigenous peoples for saying

the truth, they even wanted to imprison Berta in 2013. Yet the architects

of

Berta’s assassination are at liberty.

What are your international

advocacy goals? What do you hope to achieve here?

We hope that the actors

within the UN will meet with us and consider all our requests. We want to speak the truth, and we want it to receive the attention it

deserves. We

want our decisions as indigenous peoples to be respected. We want Convention

169 and the UN Declaration on Indigenous Peoples to be respected. In Honduras, they are not complied with, and so we have to seek

international support to pressure the State of Honduras to respect the

conventions and our rights. We await the cancellation of the Agua Zarca Project

and all the other projects authorised in the Lenca territory without free,

prior

and

informed consultation. We have to travel to ask leaders and officials to open

the door to us and to support us in demanding respect of our rights.

Do you think that this

advocacy at the international level can help you in your work? Can it be

useful?

Yes, we are very happy

because it has helped us a lot. We feel that we are not alone. At the

beginning, the Government of Honduras tried to hide the truth about Berta

Caceres’s murder, saying that it was a crime of passion, which is a lie. Thanks

to international pressure, they had to admit that it was a political crime. But

the State of Honduras continues to refuse to allow an independent international

Commission to participate in the investigations. The State is keeping the

investigations secret. We continue to call

for

an independent international Commission so that the powerful persons who

ordered the murder of Berta be properly investigated. We hope that the

international community will continue to demand it too. We are persecuted in

Honduras. The Inter-American Commission of Human Rights granted us Precautionary

Measures, but the police and military persecute and threaten us; we cannot

trust them.

We

hope to continue receiving international support to denounce the threats and

killings that we experience and that it extends to all indigenous leaders and

social movements that are threatened and attacked.

We want the Agua Zarca

Project to leave our Gualcarque River, which is sacred to us. There are international

banks that have financed this project, and we ask them to pull out

definitively.

Do you have any thoughts

on ways to make the UN more accessible and safe? Have the threats and

attacks increased as a result of your work within the UN?

It is important that the

UN listen to the voices of those of us who are being attacked and killed for defending

human rights. We are grateful that the report of the Special Rapporteur on

Indigenous Peoples exposes to the world what we suffer. We

need to have a secure space because we run risks.

Recently

we have been receiving more threats and much persecution, and that’s why we

feel unsafe. There

is still impunity for Berta’s murder, and there continue to be threats against

COPINH members for defending the Gualarque River and Lenca territory. There are

people who want to kill us so that we cannot speak the truth. But we will

continue to demand our rights, our autonomy as an Indigenous people and our

right to free, prior and informed consultation. We

hope that the UN will support us.